“We should have called a long time ago.” “We are in crisis, that’s why I called.” “It’s so crazy you wouldn’t believe it.” “I don’t know what to do.”

Within the first five minutes of the initial phone call from a caregiver, I inevitably hear one (or more) of these phrases, almost every single time. And that’s ok.

(Grammar police, I know that’s not a complete sentence.)

After a few more minutes, I usually hear “what do I do?” or “where do I even start?”

(Ok, grammar police, someone tell me the correct punctuation when a sentence is a statement but contains a question… I’ve never figured that out.)

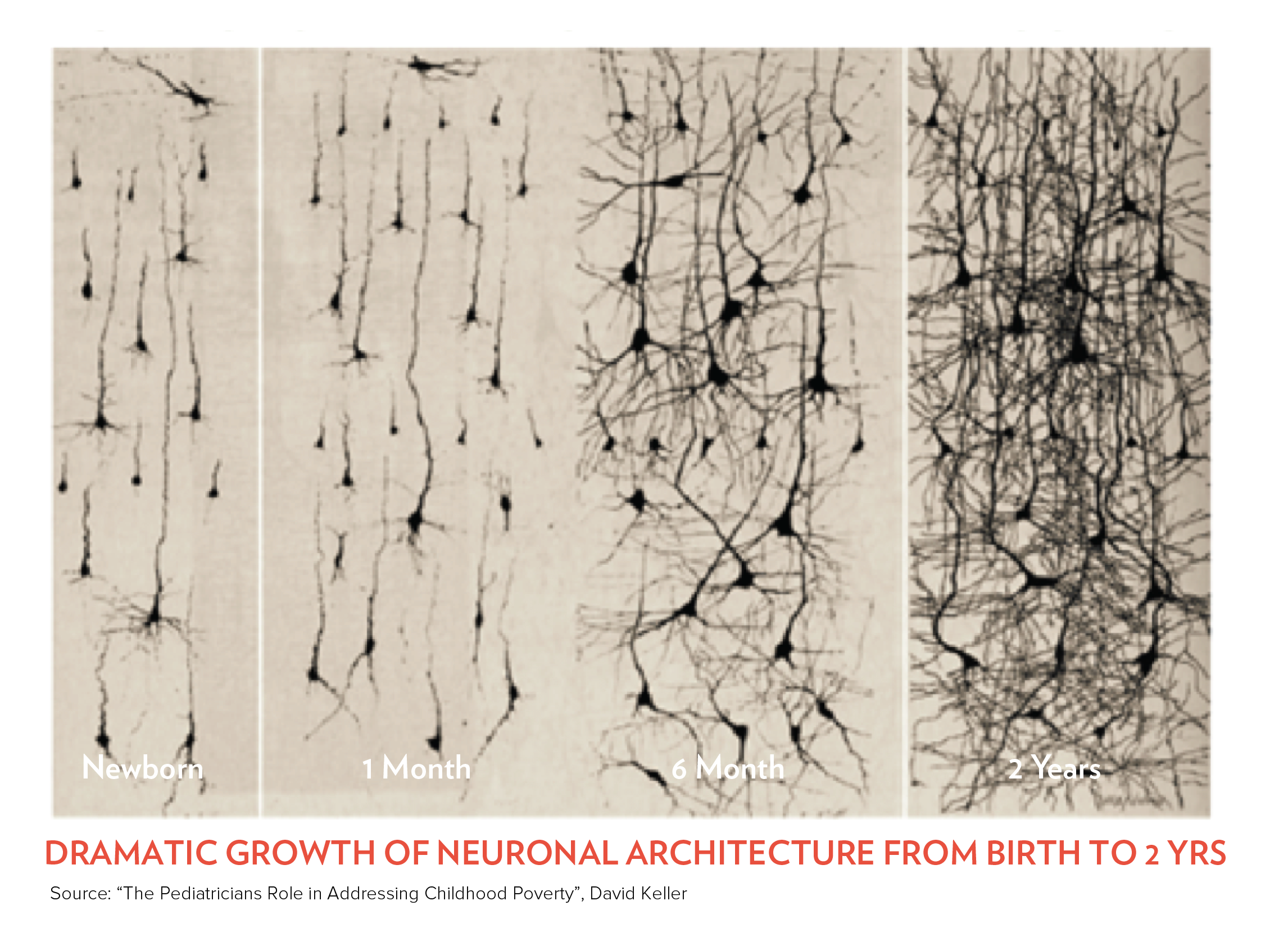

I will help the family to identify what they need right now and assist them to move out of crisis mode, also known as survival mode (when the amygdala or “little brain” is in control) so that the caregiver can engage their own prefrontal cortex

(the “big brain” that makes able logical, coherent thought processes happen.) Using my vast social work skills

(really just good, thoughtful listening.)

While this is different for each family, there is one commonality that just about every caregiver needs. It’s called the re-do.

Was that confusing? May I have a re-do? While I help each family identify their own unique needs, almost every one needs to start here, by offering “try agains” or “re-do”s.

Was that better? Thanks for the re-do!

Now I know a better way to communicate that information. I already feel more confident for the next post that I write.

That’s the power of a re-do. The first step to changing our view of unwanted behaviors as “willful disobedience” into a view of “communicating unmet needs”, caregivers need to stop the old way of dealing with those unwanted behaviors. Grounding, spanking, time outs, yelling, taking away treasured items, generally all of these actions are based in fear. The caregiver hopes the punishment or consequence is severe enough that the child will fear the consequence and not behave that way again. But if you have read anything else on this website, or done any research at all, you know that a child from a hard place has a brain that is wired differently than that of a child that didn’t come from a hard place. What children from hard places need are opportunities to learn. The mechanisms that children learn from,

(observing the environment, nurturing touch and verbal communication from a loving caregiver, opportunity to explore the world around them safely, given adequate nutrition and hydration that made them feel better)

were absent somewhere in their life or they wouldn’t be facing any of the six risk factors. Consequently, they need those learning experiences. Re-dos provide the opportunity for a child to be taught the correct way, practice it, and then move on feeling connected to, and cherished by, that caregiver.

What does a re-do look like? Imagine the five year old just walked over and yanked the toy away from their sibling. Caregiver immediately comes to the five year old

(I mean physically moves to the child, not calling the child to them)

and playfully but firmly says “Hold up there Sweetheart.”

(insert lopsided smile)

“Do you want to try that again with respect?” Caregiver then places toy back in front of sibling and demonstrates how to politely ask sibling for a turn with the toy. Five year old tries

(maybe needs a little coaching)

and is praised for the new way of doing it. High five and good job, caregiver exits scene.

Re-dos work with teens too. Imagine the 13 year old that just rolled their eyes and huffed with a foot stomp when told they could not play computer now. Before the yelling “I hate you” can even come out of the 13 year old’s mouth, caregiver gives eye contact to child and gently but firmly says, “Whoa there! Let’s try this again with respect.” Caregiver then says, “Mom/Dad/Joan can I play computer now?…

(insert change of place) Not right now…

(back to child stance) “When can I play computer?”

(switch to caregiver) “As soon as you have finished putting your clothes away you can have 15 minutes.”

Caregiver gives direct eye contact to teen, with a smile and says, “Now it’s your turn.”

Teen asks again—> caregiver says no—> teen this time instead of stomping, eye rolling, –> calmly asks when can I play–>… you get the point. High five, well done, I knew you could do it, now get the clothes put away so you can play!

A redo minimizes power struggles while increasing learning capacity, increasing confidence, improving self-regulation skills, maintains connection and trust, and reduces fear response. Because it is action-based, TBRI research has shown that 70-80% of problem behaviors can be solved at this level of playful engagement. That’s a BIG number.

Here are some tips for a successful and effective re-do.

- Be consistent – Work on a couple behaviors at a time and request a re-do every time. As a child becomes proficient on a behavior start working on new behaviors. There may be resistance in the beginning but once they get the hang of it a re-do should become a quick and easy fix, like pressing pause in the middle of a conversation to quickly correct a behavior.

- Connection before Correction – TBRI® explains that caregivers cannot influence their children to correct behavior until they have a connection with them. The better connection you have with your child the better they will respond to correction. The best and most effective way to build connection? Play together! Every day!

- Respond immediately – To request a re-do, it is recommended to respond within 3-5 seconds of the behavior, if possible.

- Stay calm– Use a calm and friendly tone of voice and body posture. Try to keep the interaction playful. Get down to your child’s level and keep eye contact. If faced with resistance parents can respond in a firmer voice without being scary. If a child becomes dys-regulated, an adult will need to help them to calm down before the child can attempt a re-do.

- Don’t lecture – Children learn best when parents speak to them at their level. Keep re-do’s short and sweet, (preferably 5 words or less, children from hard places have processing challenges) and use life value terms as reminders.

- Work Together – Caregivers should encourage their child that they are in it together, like a team. Caregivers should be helpful and supportive.

- Practice – Keep at it until they get it right. Model appropriate behavior if needed. Also incorporate re-do’s into role plays and pretend play to practice intermittently.

- Be patient –Learning a new behavior takes time. Be careful not to Relapse into old ways of responding because of your own needs (tired, frustrated, embarrassed.)

- Praise – Give your child praise for a job well done! High-fives work great too!

- Exit Scene – Afterwards press play, continue with daily activities like normal